https://www.wsj.com/news/types/keywords?mod=bigtop-breadcrumb

By Christopher Mims Wall St Journal

Updated Feb. 26, 2022 12:01 am

Type the words “battery” and “breakthrough” into your search engine of choice, and you’ll encounter page after page of links. They include breathless news articles and lofty pronouncements from battery startups.

And yet, according to scientists, engineers, startup founders and analysts, the use of the word “breakthrough” in the context of battery technology is misleading at best. Claims that the latest research finding or startup launch will bear fruit in the near future are almost always nonsense, they say.

“You don’t have to be in the field long to hear the phrase ‘Liar, liar, battery supplier,’ ” says Charlotte Hamilton, chief executive and co-founder of battery startup Conamix. The company was founded in 2014 and is pursuing technology that is being funded by venture capitalists and IARPA, a research arm of the U.S. intelligence community.

Batteries are becoming ever more critical to daily life. Their performance dictates how often people have to recharge their smartwatch or phone and are central to overcoming range-anxiety felt by drivers embracing electric cars. Power storage also is critical to the growing demand for renewable energy. All that has supercharged demand for batteries, turning the industry into one of the hottest areas for investors.

Venture capitalists last year poured almost $18 billion globally into startups that support the transition to electric vehicles, including batteries and lithium mining, according to PitchBook. In August, for example, China-based EV battery maker Svolt netted $1.6 billion in a single funding round.

Given what’s at sake, it’s easy to chalk up exaggerated claims about new battery breakthroughs to the tech industry’s propensity for hyperbole and grandstanding. A typical example: Researchers invent a tweak to a type of battery that has long shown promise but has never come close to commercialization. That gets spun into claims that an electric car with a 2,000-mile range is within reach.

“People like a breakthrough, but when we write papers we try to avoid using these kinds of words,” says Xin Li, a researcher at Harvard University whose team recently published a paper on a new kind of higher-capacity solid-state battery in the scientific journal Nature. “There are too many battery ‘breakthroughs’ in my opinion in the past 5 years, and not many can be implemented in a commercial product.”.

There are tangible costs to the hype. Investors can struggle to cut through the thicket of claims, and startups that are forthright about their results may lose out.

“It makes it very difficult to raise capital,” says Ms. Hamilton, whose company is working to change the materials for a key battery component, to pack in more energy at lower cost. “If like us you say, ‘We have the best lithium-sulfur battery in the world, but it’s not good enough for automotive applications yet,’ my claims get discounted,” she adds.

The decades since lithium-ion batteries were first commercialized in 1991 demonstrate that real breakthroughs in what they can deliver are few and far between.

“When we started Tesla in 2003, the batteries were just good enough, but what we had noticed was that they got better at about 7% to 8% a year, and had for a long time,” says Marc Tarpenning, a co-founder of the company. “It’s been 19 years, and we still haven’t had a step change in battery capacity—it just ticks along at 7% to 8% per year.”

The reasons progress has been more evolutionary than revolutionary are myriad, but they boil down to the inherent complexity of high-capacity batteries. It’s easy to take them for granted, seeing how they’re in practically every gizmo we buy nowadays. But at the molecular level, what goes on inside the average lithium-ion battery is a complex cascade of chemical reactions that—and this is the really tough part—unfold one way when the cell is charged, do the reverse when it is discharged, and must repeat the process countless times.

How Lithium Became a Hot CommodityPlay video: How Lithium Became a Hot Commodity

Demand for lithium is expected to outpace global supply as consumers switch to battery-powered vehicles. With China currently leading in processing of the vital raw material, the U.S. government is looking to boost domestic production. Photo illustration: Carlos Waters/WSJ

‘Another 8% improvement; look at that.’

— Tesla co-founder Marc Tarpenning

To recharge an iPhone is to unscramble the proverbial egg of its battery. This process is never perfect, and is the primary reason the capacity of even the best batteries degrades over time.

Many approaches that in theory could double or triple the capacity of existing batteries haven’t been made to work beyond a few charge cycles. A prime example are lithium-sulfur batteries, which on paper could have nearly 10 times the capacity of current cells. The only problem: If you make one the same way you make current batteries, it breaks down almost completely after just one or two charge cycles.

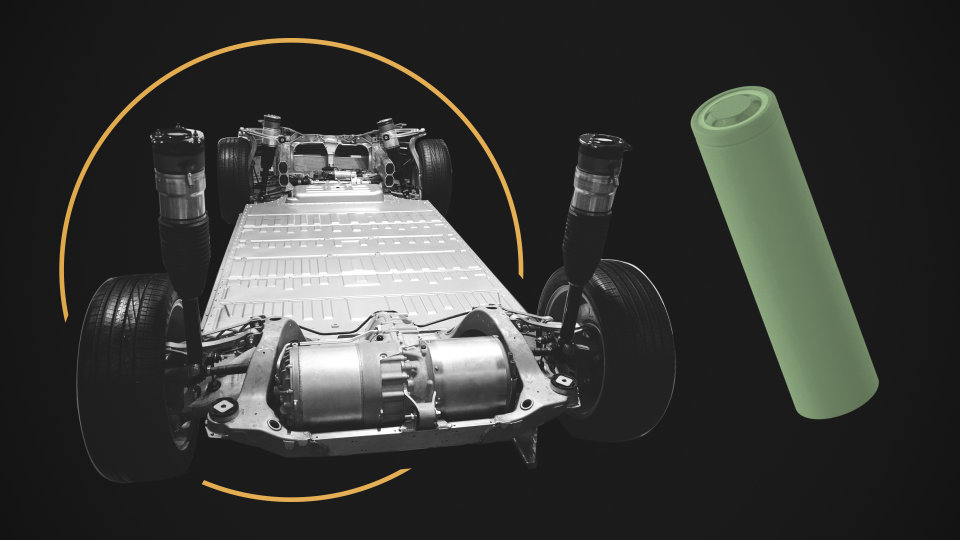

Most batteries produced today go into electric vehicles, not consumer electronics, in part because cars require so many more of them. The smallest battery pack Tesla makes contains the same amount of energy as the cells in 1,666 iPhones; an Electric Hummer is the equivalent of 7,000 of them. As a result, EVs are now the primary driver of demand for batteries, and the requirements of auto makers are the de facto standards which battery makers must meet.

And yet the requirements of auto makers are often not reflected in the way that researchers and startups report the performance of their batteries.

While it’s easy to create a battery in the lab that performs well by one measure, the way such results are reported is often a kind of sleight-of-hand, says Ms. Hamilton. Such reports tend to play down the fact that a real-world battery must perform well by at least a half-dozen different measures that matter for electric vehicles. Those include delivering power for acceleration, storing a lot of energy per gram of weight to enable long range, lasting for thousands of charge and discharge cycles, operating in a wide range of temperatures, and not catching fire too easily when damaged.

Also, batteries can’t cost too much, since their price is the primary driver of the cost of electric vehicles.

Even when a promising new battery technology can be made to work by all the measures that matter, another challenge looms just as large: production.

So much money and research and development has already been invested in existing lithium-ion battery technology that for any rival approach to catch up is almost impossible, unless it can be manufactured in nearly the same way within existing facilities, says Mr. Tarpenning.

Commercializing new battery technologies at the scale auto makers demand can require billions of dollars in investment, which must be recouped in the form of higher initial costs for these batteries, says Cory Steuben, president of automotive-manufacturing advisory firm Munro & Associates.

This isn’t to say that promising new battery technologies won’t ever be commercialized.

Many companies are continuing to do the hard work of improving existing battery technologies, though they tend not to claim their technology is a “breakthrough,” since their work leads to small improvements in performance. One such startup is Coreshell, which just announced $12 million in Series A funding, and counts Mr. Tarpenning as one of its advisers.

A big issue in automotive batteries is cooling the massive packs of individual battery cells a vehicle requires. This is critical to both performance and safety, and accounts for a significant amount of the volume and weight of these battery packs.

Coreshell is trying to commercialize a thin coating for a critical part of lithium-ion batteries that should allow them to safely operate at higher temperatures, and slow their degradation, says Jonathan Tan, the company’s CEO and co-founder.

At the other end of the spectrum of payoff and risk are the researchers plugging away at new ways of making batteries, and understanding how their different components interact. Since battery technology is dependent on complicated, multistep chemical reactions among a large number of substances, there is a great deal we still don’t know about how they work.

At Harvard, Dr. Li’s team has worked out a new way to make solid-state batteries last longer. In theory, this could make the current combinations of elements that go into batteries yield a product with much higher capacity, and way down the road, it could be used in concert with other novel chemistries, like lithium-sulfur, to take auto- and gadget-makers to some sort of high-performance battery nirvana.

But Dr. Li cautions that commercializing his team’s technology will take years, and there are many challenges remaining, not to mention the unknown obstacles which typically arise on the long path between research findings and scaled-up production.

The result of these long development cycles is that, even when battery tech “breakthroughs” finally make it to market, they might just amount to the next, incremental increase in the capacity of existing battery packs, which continue to get better all the time anyway, says Mr. Tarpenning: “By the time they finally get those things into production, it could be, ‘Oh, it’s just another 8% improvement; look at that.’ ”

Why All Those EV-Battery ‘Breakthroughs’ You Hear About Aren’t Breaking Through

In the superheated market for batteries, promising lab developments often get overhyped by startups. ‘Liar, liar, battery supplier.’

Electric vehicles are the biggest drives of demand for batteries, making auto makers’ requirements the de facto standards battery makers must meet.By Christopher Mims Wall St Journal

Updated Feb. 26, 2022 12:01 am

Type the words “battery” and “breakthrough” into your search engine of choice, and you’ll encounter page after page of links. They include breathless news articles and lofty pronouncements from battery startups.

And yet, according to scientists, engineers, startup founders and analysts, the use of the word “breakthrough” in the context of battery technology is misleading at best. Claims that the latest research finding or startup launch will bear fruit in the near future are almost always nonsense, they say.

“You don’t have to be in the field long to hear the phrase ‘Liar, liar, battery supplier,’ ” says Charlotte Hamilton, chief executive and co-founder of battery startup Conamix. The company was founded in 2014 and is pursuing technology that is being funded by venture capitalists and IARPA, a research arm of the U.S. intelligence community.

Batteries are becoming ever more critical to daily life. Their performance dictates how often people have to recharge their smartwatch or phone and are central to overcoming range-anxiety felt by drivers embracing electric cars. Power storage also is critical to the growing demand for renewable energy. All that has supercharged demand for batteries, turning the industry into one of the hottest areas for investors.

Venture capitalists last year poured almost $18 billion globally into startups that support the transition to electric vehicles, including batteries and lithium mining, according to PitchBook. In August, for example, China-based EV battery maker Svolt netted $1.6 billion in a single funding round.

Given what’s at sake, it’s easy to chalk up exaggerated claims about new battery breakthroughs to the tech industry’s propensity for hyperbole and grandstanding. A typical example: Researchers invent a tweak to a type of battery that has long shown promise but has never come close to commercialization. That gets spun into claims that an electric car with a 2,000-mile range is within reach.

“People like a breakthrough, but when we write papers we try to avoid using these kinds of words,” says Xin Li, a researcher at Harvard University whose team recently published a paper on a new kind of higher-capacity solid-state battery in the scientific journal Nature. “There are too many battery ‘breakthroughs’ in my opinion in the past 5 years, and not many can be implemented in a commercial product.”.

There are tangible costs to the hype. Investors can struggle to cut through the thicket of claims, and startups that are forthright about their results may lose out.

Workers at San Jose, Calif.-based battery startup QuantumScape.

PHOTO: NICHOLAS ALBRECHT FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL“It makes it very difficult to raise capital,” says Ms. Hamilton, whose company is working to change the materials for a key battery component, to pack in more energy at lower cost. “If like us you say, ‘We have the best lithium-sulfur battery in the world, but it’s not good enough for automotive applications yet,’ my claims get discounted,” she adds.

The decades since lithium-ion batteries were first commercialized in 1991 demonstrate that real breakthroughs in what they can deliver are few and far between.

“When we started Tesla in 2003, the batteries were just good enough, but what we had noticed was that they got better at about 7% to 8% a year, and had for a long time,” says Marc Tarpenning, a co-founder of the company. “It’s been 19 years, and we still haven’t had a step change in battery capacity—it just ticks along at 7% to 8% per year.”

The reasons progress has been more evolutionary than revolutionary are myriad, but they boil down to the inherent complexity of high-capacity batteries. It’s easy to take them for granted, seeing how they’re in practically every gizmo we buy nowadays. But at the molecular level, what goes on inside the average lithium-ion battery is a complex cascade of chemical reactions that—and this is the really tough part—unfold one way when the cell is charged, do the reverse when it is discharged, and must repeat the process countless times.

How Lithium Became a Hot CommodityPlay video: How Lithium Became a Hot Commodity

Demand for lithium is expected to outpace global supply as consumers switch to battery-powered vehicles. With China currently leading in processing of the vital raw material, the U.S. government is looking to boost domestic production. Photo illustration: Carlos Waters/WSJ

‘Another 8% improvement; look at that.’

— Tesla co-founder Marc Tarpenning

To recharge an iPhone is to unscramble the proverbial egg of its battery. This process is never perfect, and is the primary reason the capacity of even the best batteries degrades over time.

Many approaches that in theory could double or triple the capacity of existing batteries haven’t been made to work beyond a few charge cycles. A prime example are lithium-sulfur batteries, which on paper could have nearly 10 times the capacity of current cells. The only problem: If you make one the same way you make current batteries, it breaks down almost completely after just one or two charge cycles.

Most batteries produced today go into electric vehicles, not consumer electronics, in part because cars require so many more of them. The smallest battery pack Tesla makes contains the same amount of energy as the cells in 1,666 iPhones; an Electric Hummer is the equivalent of 7,000 of them. As a result, EVs are now the primary driver of demand for batteries, and the requirements of auto makers are the de facto standards which battery makers must meet.

And yet the requirements of auto makers are often not reflected in the way that researchers and startups report the performance of their batteries.

While it’s easy to create a battery in the lab that performs well by one measure, the way such results are reported is often a kind of sleight-of-hand, says Ms. Hamilton. Such reports tend to play down the fact that a real-world battery must perform well by at least a half-dozen different measures that matter for electric vehicles. Those include delivering power for acceleration, storing a lot of energy per gram of weight to enable long range, lasting for thousands of charge and discharge cycles, operating in a wide range of temperatures, and not catching fire too easily when damaged.

Also, batteries can’t cost too much, since their price is the primary driver of the cost of electric vehicles.

Even when a promising new battery technology can be made to work by all the measures that matter, another challenge looms just as large: production.

A lithium-ion battery pack on a chassis at a Volkswagen factory in Zwickau, Germany.

PHOTO: KRISZTIAN BOCSI/BLOOMBERG NEWSSo much money and research and development has already been invested in existing lithium-ion battery technology that for any rival approach to catch up is almost impossible, unless it can be manufactured in nearly the same way within existing facilities, says Mr. Tarpenning.

Commercializing new battery technologies at the scale auto makers demand can require billions of dollars in investment, which must be recouped in the form of higher initial costs for these batteries, says Cory Steuben, president of automotive-manufacturing advisory firm Munro & Associates.

This isn’t to say that promising new battery technologies won’t ever be commercialized.

Many companies are continuing to do the hard work of improving existing battery technologies, though they tend not to claim their technology is a “breakthrough,” since their work leads to small improvements in performance. One such startup is Coreshell, which just announced $12 million in Series A funding, and counts Mr. Tarpenning as one of its advisers.

A big issue in automotive batteries is cooling the massive packs of individual battery cells a vehicle requires. This is critical to both performance and safety, and accounts for a significant amount of the volume and weight of these battery packs.

Coreshell is trying to commercialize a thin coating for a critical part of lithium-ion batteries that should allow them to safely operate at higher temperatures, and slow their degradation, says Jonathan Tan, the company’s CEO and co-founder.

The smallest battery pack Tesla makes contains the same amount of energy as the cells in 1,666 iPhones.

PHOTO: MARK J. TERRILL/ASSOCIATED PRESSAt the other end of the spectrum of payoff and risk are the researchers plugging away at new ways of making batteries, and understanding how their different components interact. Since battery technology is dependent on complicated, multistep chemical reactions among a large number of substances, there is a great deal we still don’t know about how they work.

At Harvard, Dr. Li’s team has worked out a new way to make solid-state batteries last longer. In theory, this could make the current combinations of elements that go into batteries yield a product with much higher capacity, and way down the road, it could be used in concert with other novel chemistries, like lithium-sulfur, to take auto- and gadget-makers to some sort of high-performance battery nirvana.

But Dr. Li cautions that commercializing his team’s technology will take years, and there are many challenges remaining, not to mention the unknown obstacles which typically arise on the long path between research findings and scaled-up production.

The result of these long development cycles is that, even when battery tech “breakthroughs” finally make it to market, they might just amount to the next, incremental increase in the capacity of existing battery packs, which continue to get better all the time anyway, says Mr. Tarpenning: “By the time they finally get those things into production, it could be, ‘Oh, it’s just another 8% improvement; look at that.’ ”